Today we traveled to Masada, but its story is not entirely straightforward, in fact, its quite tragic on many levels. Let me give you the overview:

Today we traveled to Masada, but its story is not entirely straightforward, in fact, its quite tragic on many levels. Let me give you the overview:

- A group of religious extremists and their families escape a rebellion that the helped foment

- They take over a palace refuge

- Their enemy comes and surrounds them

- When they can no longer hold out, they all kill themselves

Yikes! Why is this a story that we celebrate? Should we venerate this place or forget it? One of the greatest gifts of our tour educator, Uri Feinberg, is his ability not to answer these questions simply and definitively. Rather, he is always trying to provide more context to see the complex stories that lay beneath the simple, judgements of something being good or bad, noble or ignoble. The same is true for Masada.

To arrive at Masada, we rose very early and boarded our bus. We traveled east from Jerusalem, snaking our way through the Judean hills down to the Jordan valley. We turned right and headed south, hugging the west bank of the Dead Sea until we would see the flat, somewhat anvil shape of Masada.

What we were looking at is a refuge created by King Harod, the last of the Jewish kings who was both remarkable builder (Cesarea, refurbishing of the Temple, Herodian, and Masada), and homicidal, megalomaniacal, paranoid, delusional, maniac. Other than that, I’m sure he was a nice guy. Perched on the top of a fairly flat mountain, surrounded by sheer cliffs of between 200-400’ high, he built Masada as a possible refuge should his position as king became untenable. Just his luck, he never needed it. But some sixty or so years later, the citizens of his kingdom did need it. The Jews were oppressed by the occupying power, Rome. We are the descendants of the Rabbis who tried to work with the Romans. However, the group that would come to occupy Masada, whom we call the Zealots, would use violence against them to throw off Roman rule. They would even use violence against fellow Jews who did not agree with them, executing several Jewish leaders publicly. In many ways, the Zealots helped foment the rebellion against Rome that they were now running away from. But run they did, to the mountain fortress of the long-dead King Harod.

What we were looking at is a refuge created by King Harod, the last of the Jewish kings who was both remarkable builder (Cesarea, refurbishing of the Temple, Herodian, and Masada), and homicidal, megalomaniacal, paranoid, delusional, maniac. Other than that, I’m sure he was a nice guy. Perched on the top of a fairly flat mountain, surrounded by sheer cliffs of between 200-400’ high, he built Masada as a possible refuge should his position as king became untenable. Just his luck, he never needed it. But some sixty or so years later, the citizens of his kingdom did need it. The Jews were oppressed by the occupying power, Rome. We are the descendants of the Rabbis who tried to work with the Romans. However, the group that would come to occupy Masada, whom we call the Zealots, would use violence against them to throw off Roman rule. They would even use violence against fellow Jews who did not agree with them, executing several Jewish leaders publicly. In many ways, the Zealots helped foment the rebellion against Rome that they were now running away from. But run they did, to the mountain fortress of the long-dead King Harod.

The Zealots snuck up and killed the Roman guards that stood watch, and then occupied the entire mountain. From the top of Masada, they could see the Dead Sea, Harod had created systems to capture fresh water which would flash-flood down from Jerusalem, they had massive storehouses of food. All-in-all, it was a decent place to hide, except for the fact that Rome was coming for them.

The Romans set up camps, the wall of which can be seen to this day. After years of waiting them out, the Romans set up a ramp, built by Jewish slaves, upon which they would send up their huge battering ram. As safe as Masada was, it didn’t stand a chance against the power of Rome.

The Romans set up camps, the wall of which can be seen to this day. After years of waiting them out, the Romans set up a ramp, built by Jewish slaves, upon which they would send up their huge battering ram. As safe as Masada was, it didn’t stand a chance against the power of Rome.

The Zealots knew that the walls would be breached, and even though they were the once who helped foment the rebellion and were only getting what, in a sense, they deserved, I couldn’t help feeling compassion for their predicament. Rather than giving up and submitting themselves to slavery, they collectively ended their lives, and rather than burning their storehouses, they left them for the Romans to find in order to show that they didn’t do so out of a lack of food.

So what do we make of this extremist group who helped foment a war and were ultimately hunted down and killed by their own hands? Perhaps one meaning of their story is not the particulars of them as Zealots, but of Israelis who of the courage and fortitude to fight back against to odds and enemies that work against them. While this can be a story of misplaced fanaticism, it can also be a story of ongoing struggle for a place for the Jewish people to survive and thrive under our own sovereignty. But this time, we come, not as Zealots, but as a nation happy to live peaceably within the community of nations. Ultimately, the meaning of Masada is our to decide.

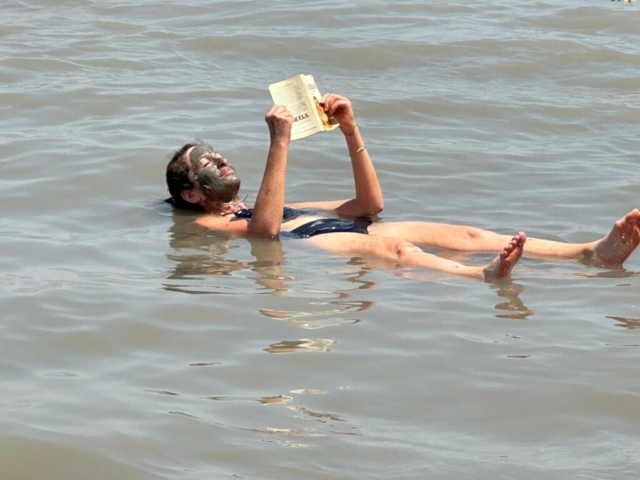

From this low-point in Jewish history, we traveled to the lowest place on earth, the Dead Sea. For decades the Dead Sea has been shrinking due to the waters that have fed it being redirected towards drinking and agriculture. Nonetheless, we made our way down to the shore and ventured in. Because the Dead Sea is so salty, many times that of the oceans, human bodies become buoyant and float when laying on its surface.

From this low-point in Jewish history, we traveled to the lowest place on earth, the Dead Sea. For decades the Dead Sea has been shrinking due to the waters that have fed it being redirected towards drinking and agriculture. Nonetheless, we made our way down to the shore and ventured in. Because the Dead Sea is so salty, many times that of the oceans, human bodies become buoyant and float when laying on its surface.  We took the mineral-laden mud on this shores of the sea and rubbed it over our bodies in the belief that our skin would look younger and healthier as a result. While I can’t vouch for the truth of that claim, there is no doubt that doing so was extraordinarily fun. We rinsed off the salt that seeped into our eyes and inflamed other open wounds, and we headed back to Jerusalem.

We took the mineral-laden mud on this shores of the sea and rubbed it over our bodies in the belief that our skin would look younger and healthier as a result. While I can’t vouch for the truth of that claim, there is no doubt that doing so was extraordinarily fun. We rinsed off the salt that seeped into our eyes and inflamed other open wounds, and we headed back to Jerusalem.

For Shabbat, we headed to a public Kabbalat Shabbat celebration at a former train station turned into an outdoor mall. A small group of singers and musicians help this religious and secular crowd to prepare for Shabbat by singing many of the Psalms and mystical poems that comprise the Kabbalat Shabbat service. Kabbalat Shabbat means “receiving Shabbat” and is meant to create the experience of a wedding celebration between the people of Israel and God. It was a joyous atmosphere that was an organic part of the public culture of the Jewish state.

We then walked back to our hotel through Yamin Moshe, the first Jewish settlement outside the protective walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. Encouraged by Moses (Moshe) Montefiore, the establishment of this settlement outside the walls allowed the growth of Jerusalem into the largest city in Israel today.

We then walked back to our hotel through Yamin Moshe, the first Jewish settlement outside the protective walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. Encouraged by Moses (Moshe) Montefiore, the establishment of this settlement outside the walls allowed the growth of Jerusalem into the largest city in Israel today.

We then enjoyed a Shabbat dinner and some singing around the Shabbat table. What a wonderful day to welcome Shabbat into our midst.